Lack of water to fight fires in southern and western neighborhoods after a major quake could result in a firestorm, like 1906 disaster.

by Thomas K. Pendergast

As the smoke clears from the devastating fires north of San Francisco that

burned more than 200,000 acres, incinerated more than 7,000 houses and killed at

least 42 people, San Francisco might notice the distant roar of its own disastrous

inferno approaching. More than 15 San Francisco neighborhoods could burn to

the ground due to a lack of water at the SF Fire Department ’s (SFFD) disposal

after a major earthquake.

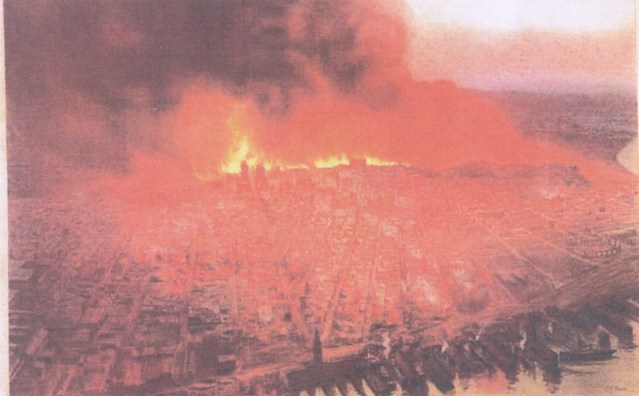

This image shows San Francisco in flames after a 7.8-earthquake struck in the early

morning hours of April 18, 1906.

A plan to expand the city’s emergency firefighting network was stalled for years

because of political interference and one city agency’s refusal to ask voters for all

of the money that is needed to protect neighborhoods in the southern and western

parts of the city. Critics say alternative plans being promoted are likely to

fail, leaving vulnerable city residents, like seniors and the disabled, to perish in

a firestorm of the city’s making or to suffer the consequences of disease and other

maladies due to a lack of fresh water after a disaster.

Experts say it is inevitable that someday there will be another earthquake on the scale of

what struck the City in 1906, a 7.8 on the Richter Scale. Now, generations after the fact,

the lessons learned from that catastrophe still resonate today as the SF Public Utilities

Commission (SFPUC) and politicians struggle to plan for the next “big one.”

The death toll for that calamity in 1906 is now estimated at about 3,000, according

to professor Charles Scawthorn, an expert on fire modeling at UC Berkeley.

Before that infamous earthquake, the City had a good, functional water supply system.

Then, the ground shook violently for almost three minutes and the domestic system’s

pipelines sustained more than 300 breaks on water mains and 23,000 breaks on service

connections. Consequently, the fire department lost water pressure at the same time that

busted gas lines sparked a conflagration, which ultimately devastated much of

San Francisco.

According to James Dalessandro, who wrote the novel “1906,” a fictional story set in San

Francisco during the earthquake and its aftermath, many people died in the fires that

followed the massive shaking, and only Navy ships pumping sea water down Van Ness

Avenue eventually stopped the wall of flames.

While researching for his book, Dalessandro discovered that within 10 minutes of the

earthquake at least 51 recorded fires broke out.

“The majority of them were in the South of Market area, which was a lot of cheap hotels

and some industrial areas,” he said.

Without water to fight the fires, the SFFD found itself helpless to react, so the fires soon

spread among collapsed buildings until it created a conflagration that swept across

the City.

“The military, in their infinite genius, decided to use dynamite to try and stop the fire by

blasting away at wood-frame buildings but all it did was spread the fire,” he explained.

“The United States Navy stopped the fire. They ran hose lines along the Embarcadero

from Van Ness toward the Ferry Building. And they ran another hose line up Van Ness

Avenue to California Street. They pumped salt water into the engines for fire fighters and

people in the neighborhood came charging out of their buildings with curtains and

blankets and towels and soaked them with salt water to beat the flames down on some of

their buildings. That’s what stopped the fire.”

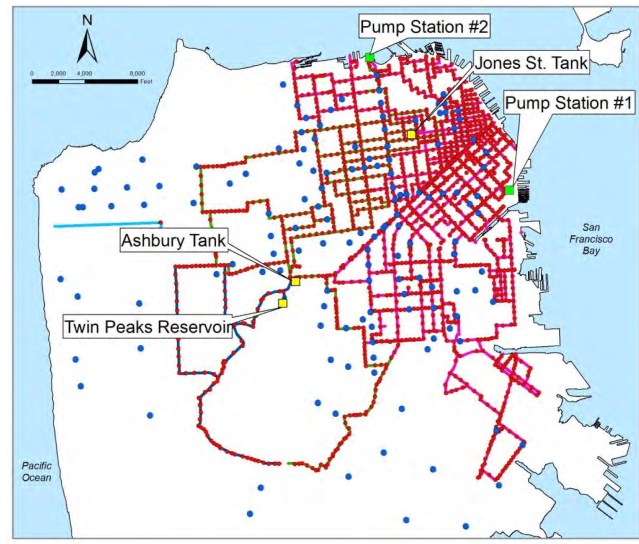

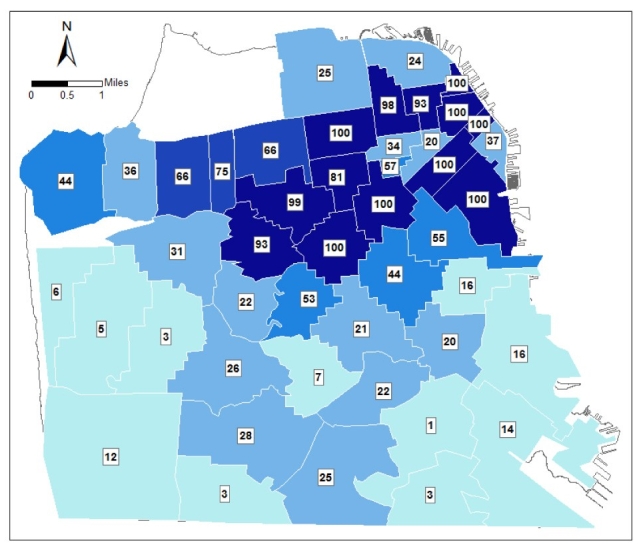

This map shows the existing Auxillary Water Supply System, which was never expanded to some 15 neighborhoods in the southern and western parts of the City.

Estimates vary, but there could be as many as 100 fires flaring up in the outer avenues

soon after a large earthquake, and many more across the city. There were 27 fires

reported after the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake, which lasted 45 seconds.

Frank Blackburn retired from the SFFD in 1991 as an assistant chief after a

32-year career with the department. He was also the director for earthquake

preparedness.

“Most people think that the earthquake did all of the damage in 1906, but

no, it didn’t,” Blackburn said. “The fires that started following the earthquake destroyed

27,000 buildings.”

Building a safety network

In the years immediately following the earthquake, city leaders designed and ordered

built the Auxiliary Water Supply System (AWSS), a network of pipelines built to

withstand a large earthquake that would be used exclusively for firefighting and was

completely separated from the regular water supply pipelines. This system of extra-

robust pipeline would be able to use both fresh water from the city’s reservoirs and

tanks, plus an unlimited supply of saltwater as well.

The fresh water supply relies on gravity to send water downhill from the Twin

Peaks Reservoir, so it does not need a pump and is not dependent on PG&E’s

electrical power, which would likely fail in a magnitude 7.8-level earthquake.

Two large pumps with independent power sources are used to push saltwater

into the AWSS as needed. The pumps can supply up to 330 pounds-per-square-inch

(p.s.i.) of pressure for firefighting throughout the AWSS. The system was designed to

provide high-pressure water within 30 minutes of a major earthquake.

The city’s white-topped fire hydrants (right) are hooked up to the city’s domestic

water supply system, while the red, blue and black-topped hydrants are a part of the

Auxiliary Water Supply System (AWSS), which is used exclusively for firefighting.

“It is a water system that is seismically designed to resist earthquakes,”

Blackburn said. “It has all kinds of contingencies and extra valves built in, so

that if you have a break it can be closed off and then you can still have a water

supply. Because we’re a peninsula and you have saltwater in the bay and the

Pacific Ocean, we have an unlimited water supply. The (AWSS) mains are heavily

constructed. They have tie rods so they don’t get pulled apart from underground

earth movement.”

The original version of the AWSS was completed by 1913. At the time most of the City

was in the north and east sections, so the AWSS now stops at 12th Avenue in the

Richmond District, 19th Avenue in the Sunset District, and at first it was not extended to

other city neighborhoods, including the Bayview Heights, Crocker Amazon, Excelsior,

Ingleside, Little Hollywood, Merced Manor, Mission Terrace, Oceanview, Outer Mission,

Outer Richmond, Outer Sunset, Parkside, Portola, Sea Cliff, Stonestown and Sunnyside.

The SFPUC includes on maps what it deems as an AWSS pipeline running from Stow Lake

to Fulton Street and then west along Fulton to 48th Avenue, but the line is not

constructed to AWSS standards and lacks adequate pressure for firefighting. At the

hydrant at 22nd Avenue and Fulton Street, the outflow pressure is in the 30 p.s.i. range,

far short of the amount needed to fight fires. The pressure increases along the line as

gravity pushes the water downhill, but the line is not pressurized and has limited use for

putting out fires.

Expanding the city’s firefighting system

In 1986, voters passed a $48 million bond measure to upgrade two saltwater pumps and

for several short AWSS extensions, down Portola Drive with a 20-inch diameter

transmission water main to Ocean Avenue, thus covering the western border of

St. Francis Wood and Balboa Terrace. Then it goes along Ocean Avenue past SF City

College and up to Mission Street in a large loop bordering the Excelsior District.

The AWSS was also extended into the Inner-Sunset southward along Seventh

Avenue and then turns west on Taraval Street. It then turns north on 19th Avenue

to Irving Street, where it travels eastward to complete the loop.

A smaller “loop” of the AWSS was put around a part of the Bay View, in the

area of Oakdale, Third and Revere streets. But the “dead end” loop has trouble

providing water to the pressure standards of the rest of the AWSS system.

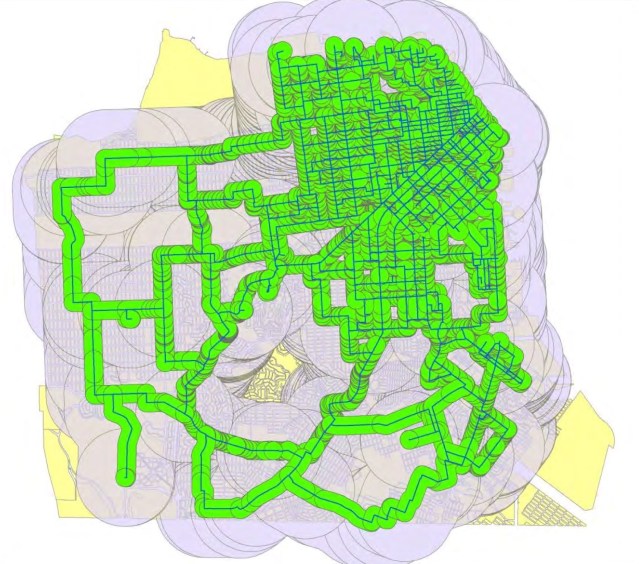

This graphic shows the expected firefighting coverage from a fully expanded AWSS. It has always been the city’s intention to expand the system throughout the City.

The need to expand the AWSS to fully encompass the city and expand into unserved

neighborhoods has been recognized for decades by city planners and firefighting

experts. The SF Civil Grand Jury recognized the importance of the AWSS in 2002.

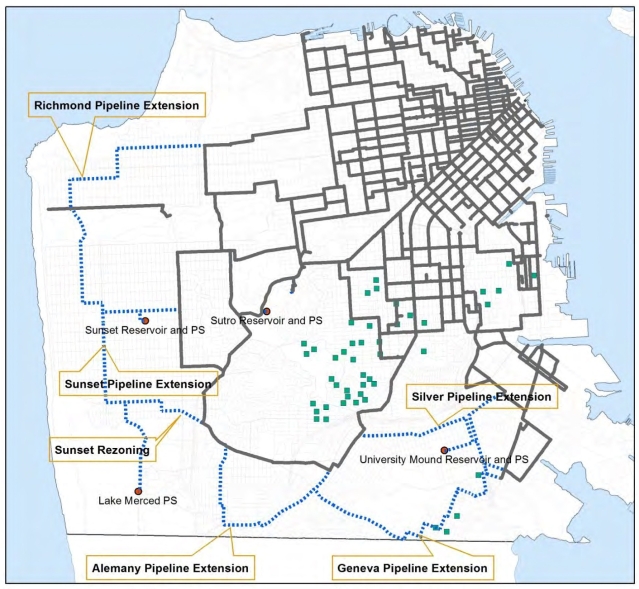

AECOM, the company hired to research proposals for expanding the AWSS, recommended this plan, which would give firefighters in the western and southern edges of the City unlimited salt water at high pressure to fight fires. Fresh water from the Sunset Reservoir and Lake Merced could be pumped into the system as needed.

A big test for the AWSS came during the 6.9-magnitude Loma Prieta Earthquake.

For the most part the system worked, but it did fail the Marina District, mostly in

liquefaction zones, so a combination of water from cisterns and fireboats pumping

saltwater was used to stop fires there before they grew too big.

San Francisco has “infirm areas,” where the ground has either been filled in

or consists mostly of loose sand. In the downtown area, the shoreline used to be

at Montgomery Street but subsequently it was filled in and the land was extended

out to the Embarcadero. This makes that, and other infirm areas like the Marina

District, vulnerable to liquefaction during an earthquake, where the ground temporarily

becomes more like a muddy liquid than a solid.

“We had five breaks South of Market,” Blackburn explained. “The high-pressure mains

(AWSS), we expect them to break in those infirm areas … In 1989 we had not motorized

all of our gate valves yet, so we had to do it manually.”

The water supply for the South of Market and Marina districts comes from the

750,000-gallon Jones Street Tank, which in turn is supplied from an AWSS

pipeline coming from the Twin Peaks Reservoir.

“Those five breaks South of Market, we were unable to close off the valves

right away because of all the chaos from the earthquake,” Blackburn said.

At the same time, all of the phone land lines went down so there were communication

problems getting the pump stations to kick in. Because of delays finding breaks, closing

off the valves and getting pumps into operation for the seawater, the total effect was to

drain the Jones Street Tank before it could be replenished.

“When the Jones Street Tank got drained, there was no water down in the

Marina,” he said.

San Francisco is divided into firefighting response areas (FRA) based on the location of fire stations. The number with each FRA shows the level of fire-fighting “reliability” percentage associated in those areas.

At this time the value of having the valves motorized became obvious. Today, major

valves are powered by batteries located nearby and are rigged to automatically

close in the event of a magnitude 6.7 earthquake or stronger. Then, once breaks

in the pipeline are located, the damaged sections can be isolated and other valves

can be opened to restore the flow of water to other parts of the City without losing

any more.

Mayor takes AWSS away from SF Fire Department, voters pass bond measure

In 2010, two significant things occurred. First was then-SF Mayor Gavin Newsom

transferring the responsibility for the AWSS from the SFFD to the SF Public

Utilities Commission, in order to save about $3.5 million in the SFFD’s budget at

a time when the economy was sputtering, and, secondly, city voters passed a $412

million bond measure to pay for earthquake preparedness measures.

Newsom used an executive order to facilitate an “interdepartmental transfer,” to

move the AWSS from the fire department over to the SFPUC, despite the objections

of the city’s fire chief and fire commission.

After the transfer, it took five years, until 2015, for the SFFD and SFPUC to

agree on a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), which spells out

which department is responsible for various duties, including opening and closing

gate valves and inspecting fire hydrants.

According to retired SF Fire Department Assistant Deputy Chief Tom Doudiet, who

worked on the MOU, the SFPUC took its time with the MOU because it was reluctant to

put anything into writing.

The $412.3 million bond measure for earthquake preparedness was passed by

San Francisco voters in 2010 to improve deteriorating pipes, hydrants, reservoirs,

water cisterns and pumps built after the 1906 earthquake; also to improve neighborhood

fire stations; and, replace the seismically-unsafe emergency command center with an

earthquake-safe building.

Although the bond language does not specifically say the money would be used

to expand the AWSS, in the Voter’s Guide from that year a statement signed by the

SF Democratic Party and paid for by the SF Fire Fighters PCA and the SF

Earthquake and Disaster Response Plan, urged voters to vote “yes” because the

bond measure “expands and strengthens our network of cisterns and pipes to ensure

that residents throughout the city have an emergency water supply for fire protection …

and will ensure that a high pressure-water supply is available to fight

fires and save lives in large buildings.”

Thomas O’Connor, president of San Francisco Fire Fighters Local 798, sent a letter to

Peskin on April 6, 2016, requesting bond money be used to extend the AWSS.

“We are greatly disturbed by the PUC’s recently published plans, under the 2010

and 2014 ESER bonds, to abandon the previously announced expansions of the

AWSS pipelines and hydrant system designated at Outer Richmond, Outer Sunset,

Alemany, Geneva and Silver Avenue extensions,” O’Connor said.

Between 2010 and 2012, the SFPUC posted maps on its website clearly showing

proposed extensions of the AWSS into the Outer Richmond District, via

California Street, and then crossing Golden Gate Park into the Outer Sunset District,

where there are connections to the Sunset Reservoir and Lake Merced.

The maps also show proposed extensions running from Ocean Avenue to

Alemany Boulevard and then along Geneva and Silver avenues out to the

University Mound Reservoir, which would be used to service parts of supervisorial

districts 9, 10 and 11, with the exception of Visitacion Valley.

In 2014 another $400 million bond was passed to improve or replace deteriorating

cisterns, pipes tunnels and related facilities to ensure firefighters have a reliable

high-pressure water supply for fires; to improve and/or replace neighborhood fire

and police stations; and replace seismically- unsafe police and medical examiner

facilities with earthquake-safe buildings.

By this time, however, SFPUC maps showing the previously proposed AWSS

extensions had been removed, but proposals to build an additional 30 water cisterns

across the outlying areas of the City were included, along with an alternative plan to

fight fires after a major earthquake; a “Flexible Water Supply System” plan that

was proposed and rejected.

After that, a “potable co-benefits” pipeline was proposed for the Sunset and

the Richmond Districts, using water from the Sunset Reservoir in an emergency.

That is part of the plan currently being developed.

There are three notable benefits to the use of cisterns: they are much cheaper to

build than AWSS pipelines, require little or no maintenance, and the water is

immediately available for fighting fires that start right after an earthquake.

But there are also major drawbacks to the use of cisterns. Once a cistern is empty

it is no longer useful as it must be filled manually from outside sources. Also, it

requires the use of a fire engine to pump the water out for short distances, up to

half a mile. But, if the fire is more than a half mile or so from the cistern, two fire engines

are required to tap a single cistern.

There are 42 fire engines in San Francisco’s fire-fighting fleet, including

three in the Richmond and three in the Sunset. Cisterns range from 10,000 gallons

to 75,000 gallons. On average, a fire engine at the scene of a fire will pump between1,000

and 1,500 gallons of water a minute.

According to Doudiet, if a firestorm envelops a neighborhood the only way to

stop it is to put up a wall of water, a water curtain, to absorb the heat and knock

down the flames. Last-ditch stands like that usually occur on wide streets or boulevards.

SFPUC unveils doomed flex hose system; plans lacking for city’s

southern neighborhoods

About the time the MOU was being signed, the SFPUC, on the advice of its

paid consultant, unveiled a plan to supplant the AWSS in unprotected areas of

the city.

The plan was called the Flexible Water Supply System (FWSS) and entailed

about 15 miles of 12-inch flexible hose being stored at the Sunset and University Mound

reservoirs for emergency water distribution. The University Mound Reservoir contains

140 million gallons of water, but only the North Reservoir was seismically upgraded,

in 2010.

David Briggs, the local and regional water system manager for the SFPUC at

the time, testified during a Board of Supervisors’ Government Audit and

Oversight Committee hearing on April 7, 2016, about the SFPUC’s confidence in

the untested system.

“Well, I think it is a solution that’s sustainable, so it may be permanent,” Briggs

said.

San Francisco Supervisor Aaron Peskin called the hearing because the SFPUC

was intending to scrap parts for the AWSS to save money, so the agency would not

have to pay rent for a lot to store the materials. The SFPUC said it had enough spare

parts for repairs of the AWSS. The flexible hose plan would have stored up to 15 miles of

12-inch flexible hose at the Sunset and University Mound reservoirs. After a large

earthquake, volunteers from the Neighborhood Emergency Response Team (NERT) were

going to be responsible for distributing the flex hose along prescribed routes.

But critics said untrained volunteers would face insurmountable obstructions

after a disaster, including earthquake debris in the roadways and the possibility of

having to work in pitch-black darkness. As well, the flex pipe would have had to been

hooked up to numerous pipes running underground on transit-critical roadways.

The unwieldy FWSS was abandoned sometime within the last year, and a new

plan recently emerged for the west side of the city, the “Potable Co-benefits” plan.

There are no plans at this time for providing emergency firefighting pipelines

like the AWSS to feed water into neighborhoods located in the southernmost part

of the city.

Critics question latest PUC post-earthquake proposal

The PUC’s current Potable Co-benefits plan has caused some skepticism amongst

firefighting experts and politicians.

The plan would run a reinforced pipe from the Sunset Reservoir westward on

Ortega Street to 41st Avenue, where it would turn north through Golden Gate

Park to Cabrillo Street, and then turn east to 29th Avenue.

A Potable Co-benefits Plan that draws water from the Sunset Reservoir for emergency firefighting is being proposed by the SF Public Utilities Commission. The line would extend from the reservoir to 41st Avenue, where it would turn north to cross Golden Gate Park to carry emergency water to the Richmond District.

According to retired Assistant Deputy Chief Doudiet, the plan is suspect because

it does not use strengthened AWSS pipe joints and the loss of pressure along the

line if lots of water is required in the Sunset, and may result in not enough pressure

to fight fires in the Richmond.

Firefighters generally need 60 p.s.i. of water pressure for effective firefighting. He

said each AWSS hydrant on a properly designed loop in the outer Richmond and

Sunset districts can replace four or five fire engines.

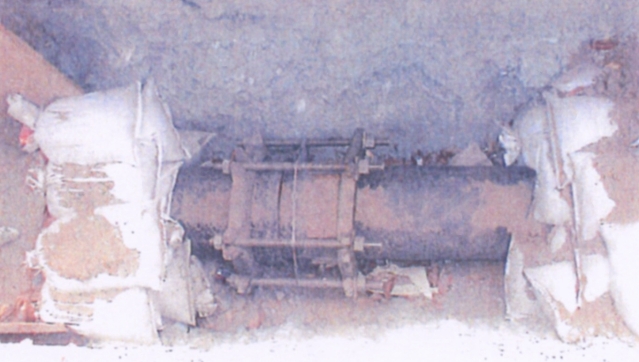

The AWSS includes ductile iron pipes and elbows with stop collars, stainless steel tie-rods and concrete thrust blocks to protect the system from high-pressure water surges.

Ductile iron pipe constructed with a “push on” type joint.

Ductile iron pipe joint “tied” with steel tie rods and bell and stop collars.

Doudiet also said it is bad city policy to use the city’s fresh water for firefighting

when it could be in short supply after a disaster.

An average three-inch firefighting hose loses about five pounds of pressure, due to

resistance, for every 50 feet of hose deployed. So, for a fire 500 feet from the water

main, there would be a drop of 50 pounds per square inch of pressure. As well, hose

resistance knocks off another 5 p.s.i. per 12 feet of elevation.

With the current proposal, getting adequate water pressure from Cabrillo Street

to elevated areas, like the Veterans Affairs (VA) center on Clement Street and 42nd

Avenue, might be difficult. Fire engines could be used to boost pressure if they

are available.

The blue-topped fire hydrants along

Fulton Street are supplied by Stow Lake

in Golden Gate Park. The gravity-fed line

must flow downhill for blocks to build

up enough pressure for limited firefighting

capability. The PUC claims, incorrectly,

that the line is part of the AWSS.

“What they would like to do is do a dual potable water system, which has not

been tested,” Richmond District Supervisor Sandra Lee Fewer said. “I feel

like the AWSS has been tested, through the 1989 earthquake. So, I’m a little cautious

because the idea that (the SFPUC) presented to us was running this potable

line from the reservoir in the Sunset all the way over into the Richmond … is a system

that has not been tested here.

“You can imagine, with all of our homes in the Richmond being built in the

early 1900s, and all-wood frames, and we’re so close to each other here, that personally

I want the best water system possible for the Richmond District, so that I’m assured that

if there is an earthquake that we have it within our capability of actually just hooking a

hose up and getting a high-pressure water system at our fingertips

to put out the fires.”

Fewer acknowledged that the AWSS is more expensive than the alternative being

proposed, but said there is little choice in the matter.

“It’s expensive, but everything’s expensive, right? That should not deter the

City from actually ensuring that our residents out here in the Richmond are safe

during a fire,” she said. “I know that it’s expensive but the cost of lives and homes

and damage and destruction is way more expensive. So, I like to err on the side of

caution.”

Sunset District Supervisor Katy Tang, on the other hand, said she has researched

the Potable Co-benefits pipeline and has confidence in it.

“The ultimate goal for our district and the City is to provide the infrastructure

necessary to allow for any neighborhood to have the most resilient system in place

for fighting fires in the event of a major disaster,” Tang said. “The west side of

town historically did not have enough protection infrastructure. However, over the

last several years, the City has invested in major projects that will significantly improve

the level of protection for our Sunset residents. The potable co-benefits pipelines have

been shown by the SFPUC and its engineering partner to provide the same level of

protection as the AWSS, but at a much lower cost.”

The total cost of the potable co-benefits pipeline running from the Sunset Reservoir to

the Richmond is estimated at $52 million, of which only $8 million is funded at this time,

according to David Myerson of the SFPUC.

Suzanne Gautier, a spokesperson for the SFPUC, said all of the PUC’s projects

are reviewed by a management-oversight committee, which is comprised of the

PUC’s general manager, Harlan K. Kelly, Jr., assistant general manager Steven

Ritchie, SFFD Fire Chief Joanne Hayes-White and the SF Department of Public

Work’s Director Mohammed Nuru.

Gautier says they will all look over various options, including the Potable Cobenefits

plan, before anything is committed.

“It is my understanding that there is a technical memorandum currently being

written and to be reviewed and once it’s completed, evaluating all of these options

and including the potable co-benefits pipeline,” Gautier said. “So, until that

memorandum is completed by an outside technical expert and additional information

is provided and is part of the analysis, there would have to be a thorough analysis

of all of those options, and that is currently underway.”

The Sunset Reservoir was built in 1938 and holds about 177 million gallons of

water, about half in each of the reservoirs’ two concrete basins. San Francisco residents

use about 65 million gallons of water a day.

The reservoir’s North Basin was structurally reinforced, at a cost of $62 million,

in 2010. Concrete pilings were driven into the hillside to stabilize the soil and 33-

foot-tall pillars holding up the roof were seismically reinforced.

According to a geotechnical investigation at the site, the soils around the reservoir

“could be susceptible to significant strength loss during a major earthquake.”

It is unclear why the South Basin was not reinforced or if it is in danger of failing

due to a large earthquake. It is also unclear if there is a gate valve between the

two basins to protect the water in the North Basin in the case of a failure at the

South Basin.

Some city supervisors whose districts are unprotected by the AWSS, including

District 7 Supervisor Norman Yee, District 11 Supervisor Ahsha Safai,

District 9 Supervisor Hillary Ronen and District 10 Supervisor Malia Cohen, did

not respond to requests for comment as of press time.

As for what the current SFFD administration thinks about the co-benefits plan,

Fire Chief Joanne Hayes-White was not available for comment, however, on her

behalf Lt. Jonathan Baxter responded, saying: “The SFFD continues to collaborate

with the SFPUC to enhance, strengthen and add further redundancy to our fire

suppression systems.”

At SF Fire Commission meetings during the past year, there has been scant

mention of the AWSS from the fire department’s chief and administrative divisions.

Use of fresh water for firefighting criticized, PUC rejects AWSS extension’s price tag

The SF Water Department, a part of the SFPUC, is currently strengthening the 167 miles

of pipes and infrastructure that brings water from the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir in the

Sierra Nevada to San Francisco taps. The overall plan is called the Water Supply

Improvement Program (WSIP).

According to water department documents, the goal of WSIP is to “restore

facilities to meet average-day demand of up to 300-million gallons a day

within 30 days after a major earthquake.”

By leveraging the city’s fresh water supply and using water mains from the city’s

domestic-water supply, the SFPUC is banking on the structural integrity of the

system to function for firefighting purposes after a major disaster.

But, firefighting experts say the plan is a recipe for disaster because the city’s domestic

water distribution system is not seismically reinforced like the AWSS, it

cannot use unlimited amounts of saltwater for firefighting, and post-earthquake fires

could deplete the city’s emergency drinking water supply, causing disease and

other problems.

Leaders at the SFPUC reportedly balked at the estimated $600-$650 million

cost to expand the AWSS to protect the city’s western and southern neighborhoods.

By using the city’s water pipes, the SFPUC saves money because domestic water pipes are

significantly cheaper to construct.

According to a report from AECOM, a private consulting firm hired by the SFPUC,

each mile of AWSS pipe costs about $19 million to install, versus approximately

$3.7 million a mile for domestic water pipes. The domestic water pipes have

“push on” seals between the joints, while the AWSS uses steel tie rods to help ensure

the joints stay together after massive shaking.

As well, fire hydrants are built to stronger specifications to withstand the extreme

pressures that can be built up with the AWSS. If the AWSS pipeline has no breaks, or

the motorized valves do their job of isolating broken segments, then high-pressure

water for fire suppression will be immediately available to firefighters.

Furthermore, the seawater supply is unlimited. A fully functioning AWSS would free

up firefighters to fight fires and perform rescue missions in collapsed buildings.

At a March 15, 2017 meeting of the SF Board of Supervisors’ Government Audit

and Oversight Committee, Supervisor Peskin asked if a cost-benefit analysis was

done comparing the co-benefits pipeline system to extending the AWSS out into

the west side areas.

A consultant with AECOM, Anne Symonds, said the initial study did include looking at

the AWSS extension into these areas; however, the PUC determined it

would be too expensive.

“The total capital cost for that alternative was in the order of $600 million,

something like that,” Symonds told the committee members. “When we presented

that to the SFPUC they said, ‘that’s not going to happen,’” to extend the AWSS

throughout the entire city. “So, our management and technical teams recommended

that we look at options that would find that nexus of where the potable system

also needs to be improved. So this is an area where we can do both things with

one project.”

“Maybe,” Peskin responded. “You’re pioneering uncharted waters. I think we

should have a real policy conversation about whether or not we should bite the

bullet and talk about a half billion dollar investment. Should we start doing more

AWSS expansions? I would like to second- guess whether we should be going

down the co-benefits road.”

Fewer said that after the March meeting she sought an independent third-party

analysis of the cost to expand the AWSS system because she is not confident about

previous cost estimates. She expects to get results in November.

“We called for an independent report on the water system and what the alternatives

(are) and a cost analysis, to share the findings,” Fewer said. “We felt that it was not an

adequate analysis, so we wanted to get an independent opinion,” she said.

Fewer also said she would support including money for further extensions of the AWSS

in a bond measure that the SFPUC is considering for the 2020 ballot.

Thomas Pendergast is a freelance reporter in San Francisco.

Paul Kozakiewicz, editor of the Richmond Review and Sunset Beacon

newspapers, contributed to this report.

FOLLOW THIS LINK TO READ THE COMMENTARY ON THIS TOPIC BY THOMAS W. DOUDIET, A RETIRED ASSISTANT DEPUTY CHIEF WITH THE SF FIRE DEPARTMENT.

FOLLOW THIS LINK FOR MORE ARTICLES AND COMMENTARY ON THIS TOPIC,

Categories: Richmond District, Richmond Review, SFFD, Sunset District

6 replies »